Peer tutoring and peer evaluation activities

increase the students’ engagement in the learning process. Student tutors

require deeper knowledge and understanding of the task which may lead to better

preparation for the classes, raising awareness, learning to share with others and

performing additional out-of-class activities, e.g. reading, watching

tutorials, etc.

Peer tutoring activities generate

significant benefits for the students. They develop reasoning and critical

thinking skills, improve self-esteem and interpersonal skills, motivate students

to communicate by various means, not only face to face but also using latest ICT

tools, so students’ digital competence may also increase.

Collaboration and teamwork are key

competences for students. The syllabi academic teachers draw up for their legal

English and business English courses always include the element of cooperation,

group work, pair work as social competences that graduates require.

The project which I introduced into my

legal English classes in spring semester 2019 was aimed at deeper engagement of

students in the learning and teaching process. Students were delegated a number

of peer tutoring tasks which were supposed to give them more responsibility,

empower them to provide feedback and keep them accountable for the quality of

the assignments carried out.

The activities which I introduced into my

classes were modelled so that they developed the productive language skills of:

- writing/drafting (legal

opinions, correspondence, blog posts, contract clauses paraphrases in plain

English, translations), and

- speaking (presentations, job

interviews).

An important element of each activity was

the preparation stage during which students familiarized themselves with the

rules, language, layouts and standards of modern writing/correspondence or

presentations.

Before they made any attempts of writing

legal opinions or paraphrasing contract clauses, they were introduced to plain

language rules, they studied model answers, analysed layout, etc. Only then

they were asked to write a document/text on their own. Peer tutoring involved

in writing activities consisted in peer correction at the first stage before

the assignment was handed in for the teacher’s grading. For writing tasks

students were also familiarized with the correction code, so that they used the

same code and the comments were understood by the authors of the texts evaluated.

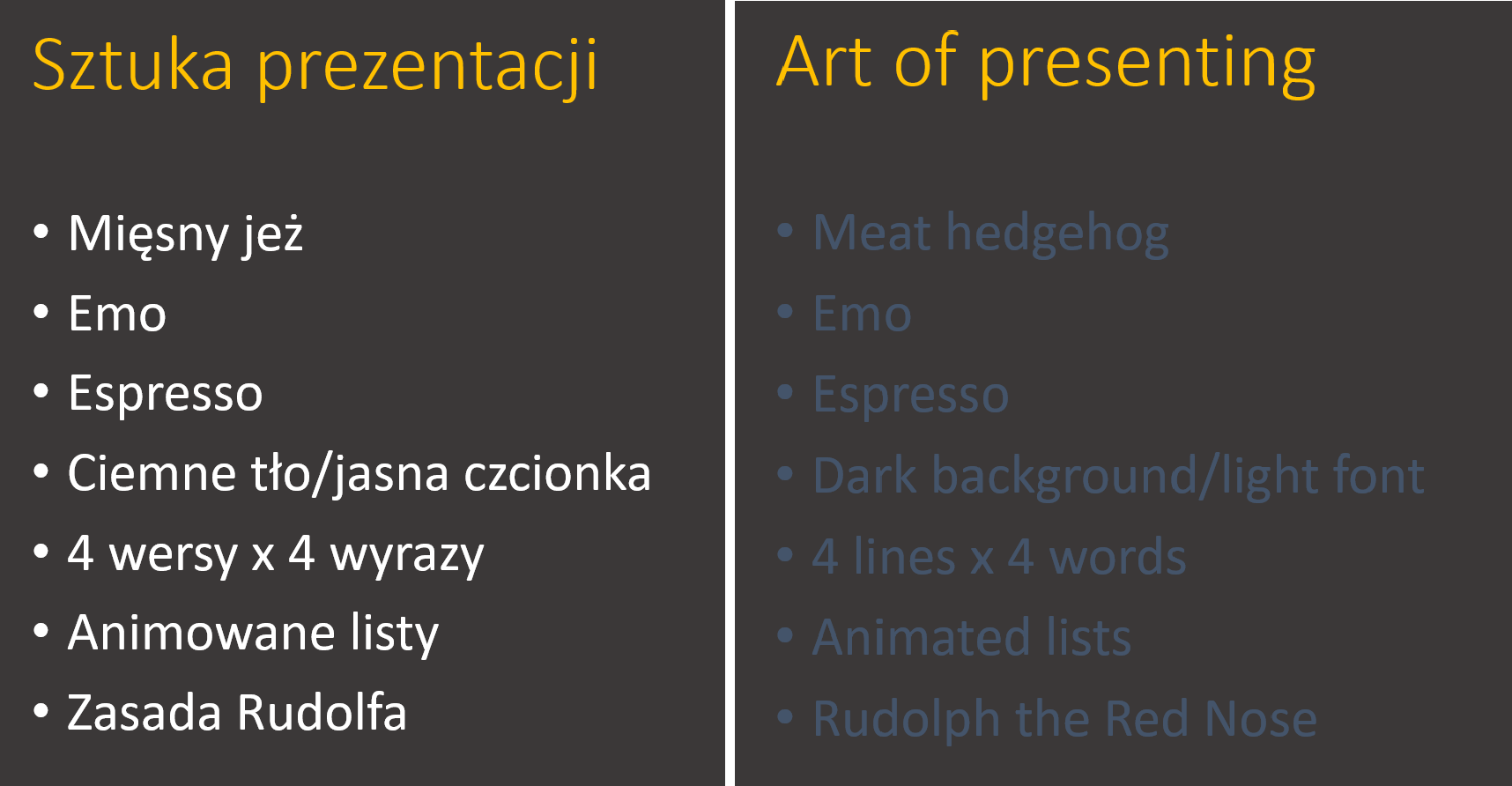

In the case of presentations students

studied the structure and the language of a presentation first and they were

sent an evaluation sheet with checklist questions to know what their peer

evaluators will be paying attention to while listening to and collecting

feedback for the presenters. During presentations the audience was asked to

make notes on the evaluation sheets under four headings: delivery,

content/structure, body language, and visual aids. After each presentation

audience commented on the strengths and weaknesses of the presentation and

asked questions, they had been asked to prepare to rehearse a question and answer

session after each presentation.

To help students

prepare for job interviews a speed interviewing session was organized. Interviewers

were given the

grid to evaluate the interviewees and had five minutes to talk to each candidate

after which time the interviewees moved to another interviewer.

As a follow up activity the interviewers group together

to discuss their marks for each candidate and choose the student with the best

score to get the job. The interviewees, on the other hand, may discuss the

questions they had to answer, which were the most challenging, what surprised

them, etc. or decide which interviewer was the most professional, asked the

most interesting questions, etc. When the students announce their choices, they

discuss the strengths and weaknesses of individual candidates and the teacher

may also give the class some feedback.

During the semester the students also prepared

their CVs. The CVs were supposed to be authentic but anonymized. I photocopied

the CVs and distributed them among students who worked in groups and were asked

to provide feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of the documents they got

and choose the best one from the collection provided. On the basis of the peer feedback

and the teacher’s feedback, students had an opportunity to polish their CVs and

resubmit them.

At the end of the semester students filled in a

short questionnaire in which they shared their opinion about peer tutoring

activities performed during their classes. Most students (73%) admitted they

improved their letter writing skills, job interviewing skills, presentation

skills. The students felt the comments they received from their peers after the

presentations were most useful (82%). More than a half of students (60%) found

the feedback concerning their letters of advice useful, while in the case of

CVs only less then one third of students (27%) valued the feed and most

students (55%) were not sure whether the feedback they received helped. Eight students

out of ten enjoyed taking the role of an evaluator and reported that they had

improved their confidence. They also confessed that positive comments were

easier to give and for most of them (78%) their peers assessment was important.

Quite interestingly, my students considered writing letters of advice as the most enjoyable of all tasks and speed interviewing as the least. The same order is reflected in the question about usefulness of the activities.

If you would like to see a detailed presentation of the results of my survey, please download the presentation.